The importance of Tea in America

Tea is often associated with Great Britain, China, or even India. Few recognize its cultural importance in America. Almost 80% of consumers in America are tea drinkers, and it is a huge share of the beverage market nationally. While it has its place on the shelves commercially, it has an even greater historical importance to the United States. This post examines two key historical events and time periods, and how integral tea was to them occurring.

The Boston Tea Party

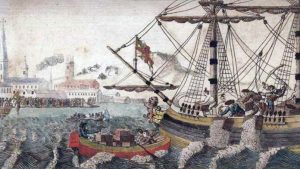

Everyone remembers learning about this in school, but few have a full understanding of the protest. On the night of December 16, 1773 a group called the Sons of Liberty dumped tea off of ships into the Boston Harbor. Most recall that it was a form of protest against British taxation, but the true story is much more complex.

The British passed the Townshend Acts starting in 1767. These acts levied taxes against the American colonies on a number of goods. Meanwhile, the East India Trading Company, one of the most important commercial institutions in Britain, was importing literally tons of tea to London, which then had to be exported to America. Initially, this tea was refunded some of the duties, but in the early 1700’s some of these refunds were cancelled. Suddenly, between the duties paid in London and the taxes paid by colonists in America, East India Tea was too expensive in the fledgling colonies. This led to a robust market for tea smugglers, as Americans would purchase tea from Dutch traders, despite the illegal nature.

Ironically, the expensive tea did not spark the protest. Rather it was England making the tea cheaper. The East India Trading Company had been importing vast quantities to tea in London, and with the diminished American market, much of it was sitting in warehouses. This large corporation was on the verge of financial meltdown. In some ways, what happened next was a 1700’s version of a government bailout.

The British government reissued refunds to the East India Tea Company. Additionally, they made provisions in the Tea Act of 1773 that allowed for direct shipments to America (no stops in London). Between the refunds and the direct shipments, prices of East India Tea plummeted, effectively undercutting the smugglers. This worked towards two goals for the British: save the floundering company, and also passively assert the right of the British to levy taxes on the American colonies. The Brits figured that with lower prices, there would be less opposition.

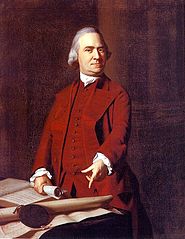

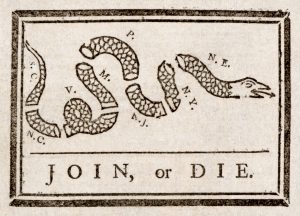

On that count, they were definitely wrong. Tea was set to be delivered to several American ports, but protests led to the ships being turned away at all ports except Boston. The people were furious about the taxation, and also because many of the colonists had worked either as smugglers, or middlemen merchants for tea coming from London. Meetings were held to discuss how to refuse delivery, but no action was taken by the colonial government. At that point, led by Samuel Adams, the Sons of Liberty took action. Many disguised themselves as Native Americans and they boarded the ships containing the dreaded tea. It took them more than three hours to dump more than 90,000 lbs of tea into the harbor. This would be more than one million dollars worth of tea in today’s money.

The tea dumping led to the Coercive Acts (also known as the Intolerable Acts). These were a series of laws designed to punish the city of Boston, and the colony of Massachusetts, for their role in causing trouble. Among other actions, it closed the Boston Harbor until satisfactory restitution was made for the lost tea. This act enraged Bostonians and American colonists up and down the 13 colonies, and is widely considered to be one of the events that triggered the American Revolution.

The Women’s Suffrage Movement

The movement for the women’s right to vote took place more than 100 years after the Boston Tea Party but was every bit as important. During the late 19th century, women had very few rights, and certainly were not allowed to vote. One issue that made it difficult to gain any traction in this movement was that women were not really able to congregate without supervision. During this time, there were very few opportunities for women to meet in private. Even going to lunch required a chaperone.

Some of this began to change with the popularity of tea houses. As teahouses began springing up, some were designed specifically for women. Finally, a place existed for groups of women to get together without their husbands or fathers overseeing their every word. These rooms turned out to be a starting point for the suffragette movement. Women meeting over tea began to talk with one another, and question why they were being treated as second class citizens. One such meeting took place at a specially designed tea house on a wealthy woman’s property.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton was living in Seneca Falls, NY. She had a social visit in her tea house with Lucretia Mott, Martha Wright, Mary Ann McClintock, and Jane Hunt in July of 1848. The women had all previously dabbled in social activism, and decided to put on a convention to discuss women’s rights and social issues. This was the birthplace of the Seneca Falls Convention. They set up the convention with only five days of formal planning, a small newspaper ad, and word of mouth advertising.

At this convention, the Declaration of Sentiments were ratified. Modeled after the Declaration of Independence, these were a list of grievances. The ninth and most incendiary one referenced women’s right to vote. It was ratified by the women at the convention, and Stanton became a lifelong fighter for women’s voting rights. Finally, the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was ratified in 1920, and women were given the right to vote. Stanton did not live long enough to see the historic day. In fact, only one of the original signers of the Declaration of Sentiments was alive for the ratification. Charlotte Pierce, who was 19 at the time of the Seneca Falls Convention, was 90 when the women’s suffrage movement finally prevailed. And to think that it all began with a simple cup of tea among friends.

References

http://www.historynet.com/seneca-falls-convention

http://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/townsend_act_1767.asp

http://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/boston_port_act.asp

http://www.eyewitnesstohistory.com/teaparty.htm

http://www.history.com/topics/american-revolution/boston-tea-party

In many countries, consumption of chamomile tea is a daily ritual, especially among older adults. In April 2015, a study was published that sought to quantify the benefits of this practice. While the Japanese are renowned for their tea drinking, this study, published in the Oxford Academic, instead focused on Mexican Americans above the age of 65.

In many countries, consumption of chamomile tea is a daily ritual, especially among older adults. In April 2015, a study was published that sought to quantify the benefits of this practice. While the Japanese are renowned for their tea drinking, this study, published in the Oxford Academic, instead focused on Mexican Americans above the age of 65. September issue of Plant Science Today. They had three different groups: one group that drank chamomile tea, one group that drank

September issue of Plant Science Today. They had three different groups: one group that drank chamomile tea, one group that drank

be known as cramping, and is experienced by up to 90% of women during menstruation. Luckily, there are already several remedies available to relieve the symptoms of these cramps. Most commonly, women are given non steroidal anti-inflammatory medications. These are usually quite effective, but roughly 1 in 10 women do not respond to these measures. For these women, alternatives are needed.

be known as cramping, and is experienced by up to 90% of women during menstruation. Luckily, there are already several remedies available to relieve the symptoms of these cramps. Most commonly, women are given non steroidal anti-inflammatory medications. These are usually quite effective, but roughly 1 in 10 women do not respond to these measures. For these women, alternatives are needed.

The pot marigold has long been thought of to have powerful medicinal properties. For years these ideas were left to mystics and non-western healers. The tide is turning, as many within the medical community are turning towards herbal remedies to avoid the rising tide of prescription drugs. This organic solution is

The pot marigold has long been thought of to have powerful medicinal properties. For years these ideas were left to mystics and non-western healers. The tide is turning, as many within the medical community are turning towards herbal remedies to avoid the rising tide of prescription drugs. This organic solution is